Babies Learning Language

Thoughts on language learning, child development, and fatherhood; experimental methods, reproducibility, and open science; theoretical musings on cognitive science more broadly.

Monday, February 16, 2026

An LLM-backed "socratic tutor" to replace reading responses

Wednesday, July 23, 2025

Book review: Elusive Cures

I'm normally an avid fiction reader, but this summer I've been on a non-fiction kick. I just finished listening to Nicole Rust's new book, Elusive Cures. The premise of the book is the simple, important question: why haven't we made more progress on understanding brain disorders using basic neuroscience? Rust's argument is that the kind of "domino chain" causal model that we use to understand many neural systems is simply mismatched to the nature of how complex systems work. Rust is a cognitive neuroscientist who is known for her work on vision and memory, but she does not lean on these areas in the book, instead broadly surveying the neuroscience of disorders including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and depression.

Although I'm mostly a cognitive scientist these days, Rust's description of the forward causal model for neuroscience immediately felt familiar from from my grad school neuroscience training. These kinds of causal systems are the ones we've made the most progress on in cognition as well: we have pretty strong models of how visual object recognition, reading, and language processing unfold in time. In contrast, processes that unfold interactively over time, such as mood, are much harder to understand this way.

I have often been skeptical of the application of complex dynamical systems theory to cognition, though Rick Dale's nice intro for the Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science did win me over somewhat. I agree that cognition is a complex dynamical system, but in practice such formalisms can often feel unconstrained. Many researchers using dynamical systems theories don't – for whatever reason – engage in the kind of systematic model comparison and evaluation that I believe is critical for cognitive modeling.

I heard that same kind of skepticism in Rust's own writing, which made it even more compelling when she made the case for the critical importance of understanding the brain as a complex dynamical system. Her discussion of the role of homeostasis in brain systems in particular was inspiring. It made me wonder why we don't apply the concept of homeostasis more to reason about social systems as well – for example, how communities maintain their educational standards in the face of policy changes or interventions. It's always a pleasure when a book sparks this kind of reflection.

In sum, I strongly recommend Elusive Cures. I found it thought-provoking and broad, with good descriptions of both individual research findings and sweeping trends. The book feels like the rare "popular" book that also effectively makes a forceful scientific argument.

Wednesday, June 11, 2025

Two summer book recommendations

After a long stint primarily reading fiction, I've been on a non-fiction kick recently and just read two books that I would definitely recommend!

Persuasion in Parallel (2022) by Alexander Coppock, a political scientist at Yale, is a scholarly monograph on how political persuasion works. It's a delightful combination of large-scale replications, strong emphasis on effect estimation and causal inference, and really thoughtful discussion of mechanisms. It starts from a replication and re-analysis of Lord, Ross, and Lepper (1979), the seminal work on political persuasion, and goes on to replicate a whole host of more recent studies. Across all of them, the key take-home is that arguments about controversial topics (e.g., gun control, abortion, etc.) operate very similarly across people with very different views: they cause small changes in attitude in the direction of the arguments, regardless of the recipient's initial views.

In statistical terms, there's very limited heterogeneity across groups in the effect of persuasive arguments. I really appreciated evidence on this heterogeneity question because often students' intuition in psychology is that everything differs based on sociodemographic characteristics; yet this intuition is rarely quantified or challenged. Coppock's analyses take a really important step in this direction.

The book is short and quite readable (especially given how data-rich it is). It's also very up front about the limitations of the work. There's also a thought-provoking final chapter on Bayesian inference and rational models of belief change that makes a number of connections to computational cognitive science that I enjoyed. Despite being an academic, I am not the sort of person who will sit down on a weekend with a monograph from another discipline for fun; this book was an exception for me because of how interesting, important, and thorough the work is.

On a heavier note, Doctored (2025), by Charles Piller (an investigative reporter with Science), is a screed about scientific misconduct in Alzheimer's research. I'm intimately familiar with replication issues in psychology, but I was still totally horrified to read about the impacts of scientific fraud in the Alzheimer's field. Piller makes a very well-researched and thorough case, working with experts on fraud and scientific reviewers. While a critique of the book by an Alzheimer's authority questions how central the fraudulent work was to the field (Lancet review), I was convinced by the later chapters of Doctored that show how pervasive image falsification has been within the Alzheimer's research enterprise. It's just awful to think that many people have been in dangerous clinical trials due to research misconduct.

The book was clearly written very fast as there is some redundancy between chapters and a bit of unnecessary stage-setting around various researchers' grandparents (perhaps reflecting a pivot from an earlier vision of the book where certain people were more important to the narrative). But the substance of the scientific critique is so compelling – and honestly terrifying – that I was more than happy to overlook a few minor weaknesses in the prose. Definitely recommend.

Tuesday, December 3, 2024

Four papers I'm sad never to have published

One of the saddest things in academic research is an abandoned project. You pour time, effort, and sometimes money into a piece of research, only to feel that it has not been released into the world to make an impact. Sometimes you don't finish an analysis or write a paper. But I would argue that the saddest situations are the projects that came closest to being published – these are "near misses."*

This sadness can also have practical consequences. If we abandon projects differentially because of their results – failing to report negative findings because of a belief that they would be uninteresting or hard to publish – then we get a bias in the published literature. We know this is true – but in this post I'm not going to focus on that. I'm thinking more about inadvertent near misses. The open science movement – and in particular the rise of preprints – has changed the field a lot in that these near misses are now visible again. So I'm writing this post in part to promote and discuss four projects that never saw journal publication but that I still love...

I'm a researcher but I'm also (maybe primarily) an advisor and mentor, and so this kind of thing happens all the time: a trainee comes into my lab, does a great project, writes a paper about it, and then moves on to a new position. Sometimes they stay in academia, sometimes they don't. Even if we submit the manuscript before they leave, however, it frequently happens that reviews come back after they are distracted by the next stage of their life. Unless I take over the writing process, things typically remain unpublished.

But the worst thing is when I abandon my own work because I'm too busy doing all that advising and teaching (and also getting grants to do the next shiny thing). Sadly this has happened many times over the past 15 years or so that I've been a faculty member. I simply didn't have the fortitude to get the paper through peer review and so it lingers as something interesting but unrevised – and perhaps fatally flawed (depending on whether you trust the reviewers). Here are my four biggest regrets.

1. A literature review on computational models of early language learning. This was the first chapter of my dissertation initially, and I revised it for a review journal, hoping to do something like Pinker's famous early review paper. It was reviewed by two people, one nativist and one empiricist. Both hated it, and I abandoned it in despair. I still like what I wrote, but it's very out of date now.

2. A huge dataset on children's free-viewing of naturalistic third-person dialogue and how it relates to their word learning. I loved this one. These experiments were my very first projects when I got to Stanford – we collected hundreds of kids worth of eye-tracking data (with an eye-tracker bought with my very first grant) and we were able to show correlational relationships between free-viewing and word learning. We even saw a similar relationship in kids on the autism spectrum. This paper was rejected several times from good journals for reasonable reasons (too correlational, kids with ASD were not well characterized). But I think it has a lot of value. (The data are now in Peekbank, at least).

3. A large set of experiments on reference games. Noah Goodman and I created the Rational Speech Act (RSA) model of pragmatic processing and this was a big part of my early research at Stanford. I spent a ton of time and money doing mechanical turk experiments to try to learn more about the nature of the model. This manuscript includes a lot of methodological work on paradigms for studying pragmatic inference online as well as some clever scenarios to probe the limits (there were 10 experiments overall!). Sadly I think I tried to make the manuscript more definitive than it should have been – by the time I finally submitted it, RSA already had many variants, and some of the formal work was not as strong as the empirical side. So reviewers who disliked RSA disliked it, and reviewers who liked RSA still thought it needed work.

4. A simplified formal model of teaching and learning. This one was an extension of the RSA model for teaching and learning scenarios, trying to get a handle on how teachers might change their messages based on the prior beliefs and/or knowledge of the learners. I was really proud of it, and it shapes my thinking about the dynamics of teaching to this day. Lawrence Liu started the project, but I did a ton more analysis several years later in hopes of making a full paper. Sadly, it was rejected once – reviewers thought, perhaps reasonably, that the policy implications were too big a stretch. By the time I submitted it to another journal, a bunch of other related formal work had appeared in the computer science literature. Reviewers the second time asked for more simulations, but I was out of time and the code had gotten quite stale because it depended on a very specific tech stack.

I hope someone gets a little pleasure or knowledge from these pieces. I loved working on all four of them!

----

* I just learned that there is a whole literature on the psychology of near misses, for example in gambling or with respect to emotions like relief and regret.

Some thoughts on ManyBabies 4

Three ManyBabies projects - big collaborative replications of infancy phenomena - wrapped up this year. The first paper came out this fall. I thought I'd take this chance to comment on what I make of the non-replication result.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/desc.13581

First, off - this study was a SUCCESS! We got the community together to plan a replication study and then we got 37 labs and 1000 babies to do a complicated study and we pulled it off. That's a huge win for team science! Major kudos to Kelsey, Francis, and Kiley.

In case you're wondering about the status of the other projects, here's a summary slide (already shared right after ICIS). MB3-4 yielded null effects; MB2 is complicated... preliminary analysis shows the predicted effect but an even bigger, unpredicted effect in the control condition.

Monday, March 27, 2023

Domain-specific data repositories for better data sharing in psychology!

Why do LLMs learn so much slower than humans?

Recent progress in AI is truly astonishing, though somewhat hard to interpret. I don't want to reiterate recent discussion, but @spiantado has a good take in the first part of lingbuzz.net/lingbuzz/007180; l like this thoughtful piece by @MelMitchell1 as well: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2300963120.

Many caveats still apply. LLMs are far from perfect, and I am still struggling with their immediate and eventual impacts on science (see prior thread). My goal in the current thread is to think about them as cognitive artifacts instead.

For cognitive scientists interested in the emergence of intelligent behavior, LLMs suggest that some wide range of interesting adaptive behaviors can emerge given enough scale. Obviously, there's huge debate over what counts as intelligent, and I'm not going to solve that here.

But: for my money, we start seeing *really* interesting behaviors at the scale of GPT3. Prompting for few shot tasks felt radically unexpected and new, and suggested task abstractions underlying conditional language generation. At what scale do you see this?

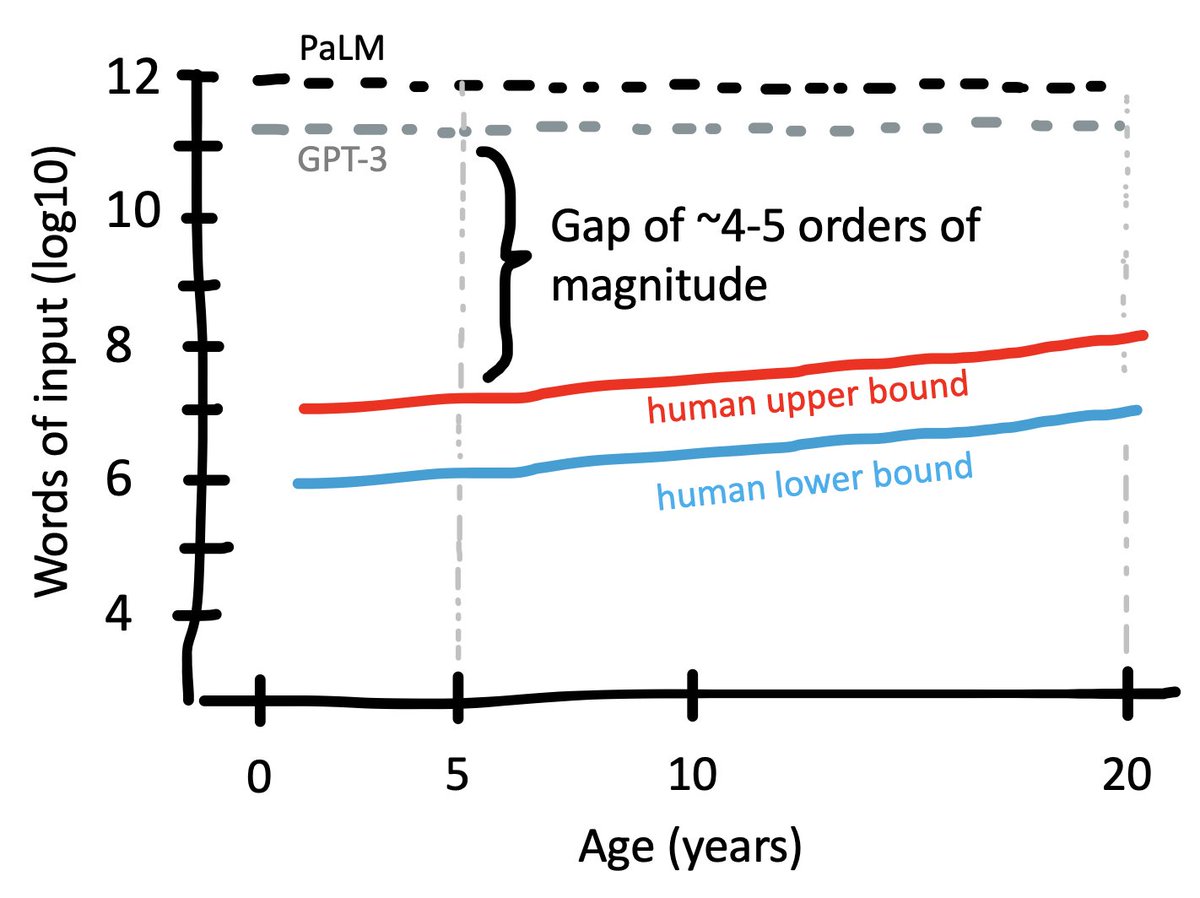

GPT-3 was trained on 500 billion tokens (= .75 words). So that gives us ~4e11 words. PaLM and Chinchilla are both trained on around 1e12 words. We don't know the corpus size for GP4-4 (!?!). How do these numbers compare with humans?

Let’s start with an upper bound. A convenient approximation is 1e6 words per month for an upper bound on spoken language to a kid (arxiv.org/pdf/1607.08723…, appendix A or pnas.org/doi/abs/10.107…). That's 2e8 words for a 20 year old. How much could they read?

Assume they start reading when they’re 10, and read a 1e5-word book/week. That’s an extra 5e6 million words per year. Double that to be safe and it still only gets us to 3e8 words over 10 years.

Now let's do a rough lower bound. Maybe 1e5 words per month for kids growing up in a low-SES environment with limited speech to children (onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.11…). We don't get much of a literacy boost. So that gives us 5e6 by age 5 and 2e7 by age 20.

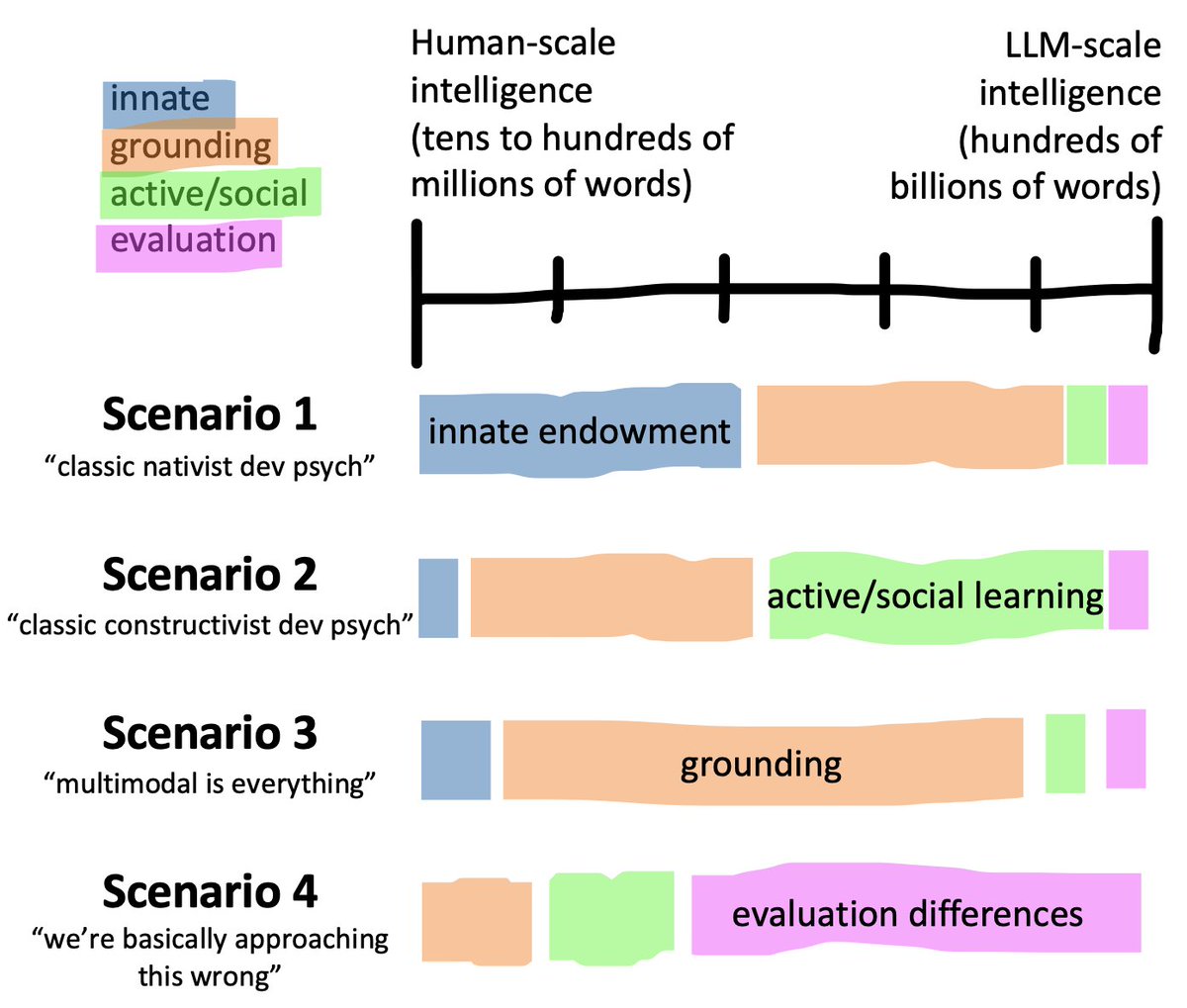

Factor 3: active, social learning. Humans learn language in interactive social situations, typically curricularized to some degree by the adults around them. After a few years, they use conversation to elicit information relevant to them.