(This post is joint with Rose Schneider, lab manager in the Language and Cognition Lab.)

For toddlers, the ability to communicate using words is an incredibly important part of learning to make their way in the world. A friend's mother tells a story that probably resonates with a lot of parents. After getting more and more frustrated trying to figure out why her son was insistently pointing at the

pantry, she almost cried when he looked straight at her and said, “cookie!” She was so grateful for the clear communication that she gave him as many cookies as he wanted.

We're interested in early word learning as a way to look into the emergence of language more broadly. What does it take to learn a word? And why is there so much variability in the emergence of children's language, given that nearly all kids end up with typical language skills later in childhood?

One way into these questions is to ask about the content of children's first words. Several studies have looked at early vocabulary (e.g. this nice one that compares across cultures), but – to our knowledge – there is not a lot of systematic data on children's absolute first word.* The first word is both a milestone for parents and caregivers and also an interesting window into the things that very young children want to (and are able to) talk about.

One way into these questions is to ask about the content of children's first words. Several studies have looked at early vocabulary (e.g. this nice one that compares across cultures), but – to our knowledge – there is not a lot of systematic data on children's absolute first word.* The first word is both a milestone for parents and caregivers and also an interesting window into the things that very young children want to (and are able to) talk about.

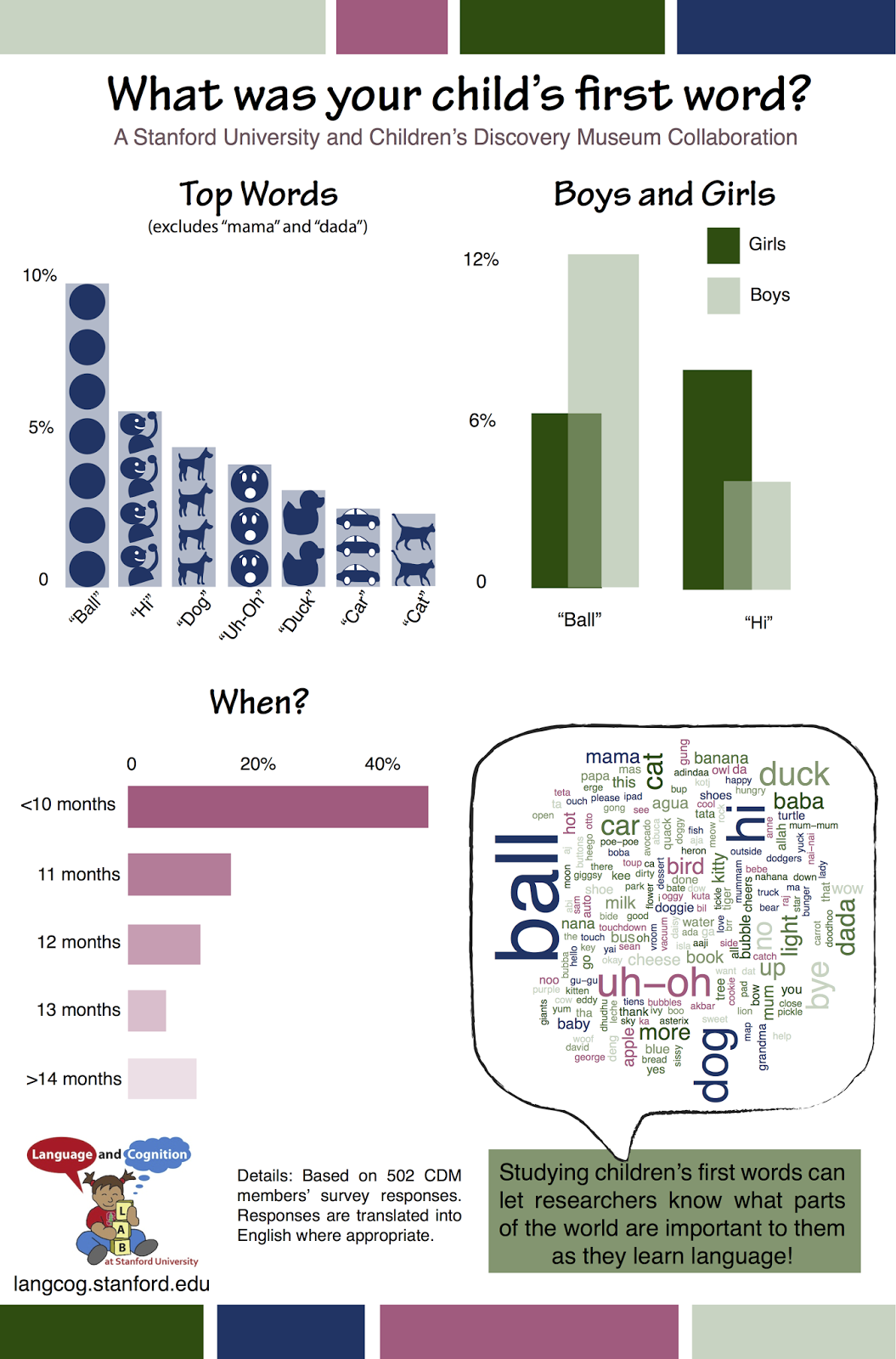

To take a look at this issue, we partnered with Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose to do a retrospective survey of children's first word. We're very pleased that they were interested in supporting this kind of developmental research and were willing to send our survey out to their members! In the survey, we were especially interested in content words, rather than names for people, so for this study, we omitted "mama" and "dada" and their equivalents. (There are lots of reasons why parents might want these particular words to get produced – and to spot them in babble even when they aren't being used meaningfully).

We put together a very short online questionnaire and asked about the child's first word, the situation it occurred in, the age of the child, the age of the utterance, and the child's current age and gender. The survey generated around 500 responses, and we preprocessed the data by translating words into English (when we had a translation available) and categorizing the words by the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) classification, a common way to group children's vocabulary into basic categories. We did our data analysis in R using ggplot2, reshape2, and ddply.

Here's the graphic we produced for CDM:

We put together a very short online questionnaire and asked about the child's first word, the situation it occurred in, the age of the child, the age of the utterance, and the child's current age and gender. The survey generated around 500 responses, and we preprocessed the data by translating words into English (when we had a translation available) and categorizing the words by the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) classification, a common way to group children's vocabulary into basic categories. We did our data analysis in R using ggplot2, reshape2, and ddply.

Here's the graphic we produced for CDM:

We were struck by a couple of features of the data, and the goal of this post is to talk a bit more about these, as well as some of other things that didn't fit in the graphic.

First, the distribution of words seemed pretty reasonable, with short, common words for objects ("ball," "car"), animals ("dog," "duck" – presumably from bathtime), and social routines ("hi"). The gender difference between "ball" and "hi" was also striking, reflecting some gender stereotypes – and some data – about girls' greater social orientation in infancy. Of course, we can't say anything about the source of such differences from these data!

Another interesting feature of the data was the age distribution we observed. On parent report forms like the CDI, parents often report that their children understand many words even in infancy, with the 75th percentile being reported to know 50 words at 8 months. While there is some empirical evidence for word knowledge before the first birthday, this 50 word number has always been surprising, and no one really knows how much wishful thinking it includes. The production numbers for the CDI are much lower, but still have a median value above zero for 10-month-olds. So is this overestimation? Probably depends on your standards. M, Mike's daughter, had something "word-like" at 10 months, but is only now producing "hi" as a 12-month-old (typical girl).

One possible confound in this reporting would be parents misremembering the age at which their child first produced a word, perhaps reporting systematically younger or older ages (or even ages rounded more towards the first birthday) as the first word recedes into the past. We didn't find evidence of this, however. The distribution of reported age of first word was the same regardless of how old the child was at the time of reporting:

Now on to some substantive analyses that didn't make it into the graphic. Grouping our responses into broad categories is a good way to explore what classes of objects, actions, etc., were the referents of first words. While many of the words we observed in parents’ responses were on the CDI, we had to classify some others ad-hoc, and still others we were unable to classify (we ended up excluding about 50 for a total sample of 454, 42% female). Here's a graph of the proportions in each category:

There are some interesting ways to break this down further. Note that girls generally are a few months ahead, language-wise, so analyses of age and gender are a bit confounded. Here's our age distribution broken down by gender:

As expected, we see girls a bit over-represented in the youngest age bin and boys a little bit over-represented in the oldest bin.

That said, here are the splits by age:

and gender:

As expected, we see girls a bit over-represented in the youngest age bin and boys a little bit over-represented in the oldest bin.

That said, here are the splits by age:

Overall, younger kids are similar to older kids, but are producing more names for people. Older kids were producing slightly more vehicle names and sounds, but this may be because the older kids skew more male (see gender graph, where vehicles are almost exclusively the provenance of male babies). The only big gender trends were 1) a preference for toys and action words for the males and 2) a general broader spread across different categories. This second trend could be a function of boys' tendency to have more idiosyncratic interests (in childhood at least, perhaps beyond).

Overall, these data give us a new way to look at early vocabulary, not at the shape of semantic networks within a single child, but at the variability of first words across a large population. We invite you to look at the data if you are interested!

Overall, these data give us a new way to look at early vocabulary, not at the shape of semantic networks within a single child, but at the variability of first words across a large population. We invite you to look at the data if you are interested!

---

Thanks very much to Jenni Martin at CDM for her support of our research!

* What does that even mean? Is a word a word if no one understands or recognizes it? That seems pretty philosophically deep, but hard to assess empirically. We'll go with the first word that someone else, usually a parent, recognized as being part of communicating (or trying to communicate).

Interesting post -- how controversial though is variability in child language development? I have had some conversations with eminent researchers who have insisted quite forcefully that development proceeds in a very regular and uniform way across individuals and across languages.

ReplyDeleteAnd I know there was some pushback on the Fenson et al study you linked to.

It seems like there are different sorts of variability that you could look at.

Hi Alex,

DeleteThanks for the comment. I guess I'd consider variability in vocabulary development an established fact. Many labs have replicated this variability (and shown that measures of vocabulary from eye-tracking to behavioral paradigms and parent report are reliable and valid).

Grammatical development is more controversial, certainly, because some of the theoretical debates mean that measures are not as well worked out. But I'd go back to Bates's work suggesting that many grammatical developments appear to be contingent on the growth of the lexicon - you can't really figure out grammar until you know some words. So you variability in one feeds into variability in the other.

Given the difficulty of understanding small children, parental expectations may be driving some of the gender differences?

ReplyDeleteDefinitely - wishful thinking can make random babble into "mama." I expect parents would be more likely to make "ba" into "ball" for a boy and "bye" for a girl...

DeleteActually, we could test whether gender effects are more prevalent in words with larger phonological neighborhoods. That certainly seems to be the case with "ball" as it's close to "bye" and "baby." For "hi" I'm less certain. Anecdotally, M does the dipthong in "hI-e" really clearly. She also uses it in communicatively appropriate ways...

Also, do you know any longitudinal studies of kids who don't speak until they are quite old, and then speak in complete sentences? I have a low-N observation that they may stay inhibited / careful through adulthood, but the only other person I've asked about this is Spelke & she didn't know of any such studies.

ReplyDeleteI don't know anything about this offhand (aside from the apocryphal Einstein story about him bursting out into fully-formed sentences at some late age).

DeleteMy impression is that most late-talkers catch up via the normal trajectory of vocabulary growth and then grammatical development, e.g.:

http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=psych_pubs

There are aspects of temperament and personality that stay constant from infancy to adulthood, however (e.g. see Kagan's work on this), so those variables - rather than anything happening in the children's language development - might explain your observation. Many kids are shy to talk around strangers, as well, especially when their language is slow relative to peers.

Counting Einstein :-), I know 3 cases of very late language acquisition (really expression; one was a next-door neighbour when we were kids) & all were associated with complete sentences when language was finally expressed, and the one I know as an adult is still slow to speak sentences in foreign languages despite good vocabulary and great phonology / accent. I'm sure some "personality" trait is associated with inhibition of social performance, but I'm more familiar with the abstraction of action selection mechanisms than that of personality psychology. I guess I'm wondering if there is basic biological / neurological diversity in social risk taking strategies --- that is, the levels of confidence or conformity necessary to express social acts.

Delete